Happy New Year Everyone!

Let’s hope 2021 will be more enjoyable than in 2020.

I would like to thank those who responded to our offer in November. We look forward to meeting with you in the near future. We still have a couple of slots left, so please check out our special offer that The Huddleston Group is making to organizations, like yours. See the link below for more details. But hurry! Time is limited!

This month, we are going to talk about an issue many of us try to avoid most of the time: our board–staff relationships and responsibilities. Enjoy.

Do You Have A Healthy Organization?

A strong and healthy board-staff partnership provides flexible and resilient leadership that contributes positively to an organization’s overall impact. A weak or dysfunctional partnership impedes the effectiveness of both the board and the executive and puts the organization at risk in a number of ways – lack of strategic alignment or direction, executive turnover, a toxic organizational culture, and the list could go on and on.

I have served on several nonprofit boards of directors and written several articles about those and other leadership experiences. I’ve learned that building and sustaining high-functioning governing bodies is arduous, time-consuming work, but it’s worth the effort. If they are run well, they can bolster an organization’s revenues, provide access to influential figures, inspire confidence in stakeholders, help manage risks, improve leaders’ performance, and contribute to the crafting of a compelling mission and strategy.

Sadly, many nonprofit boards miss out on these benefits and are more or less dysfunctional. I make this assessment based on a recent Urban Institute report and my nearly four decades of work in the field. People usually don’t like to draw attention to the fact that they were part of such a group.

In order to cultivate the trust, respect, candor, and communication that characterize a healthy partnership between a board and staff members, BoardSource recommends a number of key practices, including the following:

- Regular check-ins between the executive and chair; Open and consistent communication channels between the executive and the board chair help build a strong working relationship and bring to the surface issues and challenges before they get bigger.

- A commitment to “no surprises”; For both the executive and the board, it’s important to share openly and honestly, including when there’s bad news. This is especially important between the executive and the chair, who set the tone for the relationship between the executive and the board as a whole.

- Thoughtful reflection on performance; One of the board’s essential responsibilities is to annually evaluate the executive’s performance and provide honest feedback on successes and challenges. Equally important, however, is that the board assesses its own performance. In addition to helping strengthen board performance, this protocol demonstrates the board’s commitment to shared leadership and responsibility.

Since your board is full of different people who all want different things, setting up and communicating clear expectations is a good idea for all involved. Your board members should be aware of their roles and responsibilities towards each other as well as to the organization.

It’s important to note, as well, that expectations will vary from organization to organization. For example, the board members of a nonprofit organization are expected to be major donors and fundraisers for the nonprofit and understand additional legal expectations and standards.

The board’s role is essential because the board of directors’ involvement, commitment, sense of partnership, and strength make a critical difference in an organization’s ability to continue and to grow. Chief executive officers and staffs – the transients in the nonprofit world – come and go, but strong boards that infuse their membership with new blood on a regular basis are the constants and can provide the stability needed in organizational life. Moreover, only boards are capable of selecting new leadership, holding the organization accountable, and serving as the principal guardian of the nonprofit organization’s welfare.

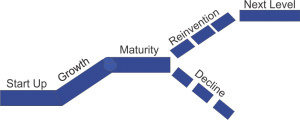

If staff and board leadership are strong and intent on making change occur, however, the board may develop a strong, new, workable dynamic within three years – but probably not much before. The board seems to be the slowest part of an organization to change and the slowest to discover and operate on a new dynamic that is relevant to the lifecycle of the organization itself.

My years of experience have shown me that the key to a healthy and involved board is to emphasize the importance attached to the orderly rotation of board members. Bylaws should specify the length of terms and the consecutive number of terms that a board member can serve. There are losses as well as gains in this process because boards lose the fine, dedicated people who started the organization and who carry its institutional memory. But change is essential to enabling boards to keep up with the times and renewing and revitalizing them so that they serve the organization well as it grows. Moreover, there appears to be no other way to deal with inactive members or, worse, founding members who block the reforms that are necessary for organizational growth. Only with fresh blood and a constant source of new energy can boards move reasonably easily through the phases necessary for the organization’s growth and development.

Furthermore, having a solid understanding of the dynamic relationship between the board and the chief executive officer is beneficial so that the board and chief executive officer have the necessary information they need to fulfill their complementary roles. Finally, strategic planning and generative thinking is something that the board can regularly engage in as a means of creating a unified and effective vision for the organization. This process engages board members in supporting the purpose of the organization by re-conceptualizing the problem that the organization needs to address. By following some of these strategies and principles, boards and board members can become more effective at managing their unique roles and providing sound and responsible governance to nonprofits.

Board members who volunteer to work alongside professional staff members can amplify a nonprofit’s work and gain a deeper understanding of the organization. But when this devolves into their bossing the staff around, making decisions on the staff’s behalf, and providing the board with negative evaluations of employees based on potentially brief glimpses of their work, it can create a toxic environment and lead to team members becoming passive, secretive, or demoralized. Board members who are used to being decision-makers and leaders on their regular jobs are especially prone to acting as if they are or should be in charge. I once volunteered for an organization where the staff told me that they had two bosses – the chief executive officer and a board member who took an interest in their role. In order to avoid creating such confusion, board members need to understand that when they reach out to work with the staff, they are volunteers who happen to be board members rather than board members who are there to supervise anyone or order people around. Their role is to help, advise, and learn. There should also be limits on what directors can tell the board about what they learn while volunteering.

In conclusion, a lack of board members’ engagement in their duties is a problem that many boards face; it leads to a decreased ability of boards to carry out their functions. Some of the problems with board engagement can be attributed to board members being unclear about their role as trustee or confusion about the roles and responsibilities of the board in relation to the organization and staff. In order to become more effective and engage, boards should consider who they are responsible to and define their purpose and role. Then, boards need to strategically recruit board members and provide orientation, ongoing training, and education to members. Boards also need to continuously evaluate their own performance in achieving the goals that they set for themselves and find ways to grow and improve.

In my experience, a board is not and cannot be static. Instead, it must change and evolve as the organization changes and grows. Roles, functions, and memberships need to be altered in order to meet new challenges that the nonprofit organization itself confronts. Many of these changes in board roles, functions, and memberships are predictable because they are natural consequences of organizational growth. If not, the organization will decline and possibly cease to exist. Running a successful nonprofit takes an active board of directors and a dedicated staff that is led by a capable chief executive officer.

In my experience, a board is not and cannot be static. Instead, it must change and evolve as the organization changes and grows. Roles, functions, and memberships need to be altered in order to meet new challenges that the nonprofit organization itself confronts. Many of these changes in board roles, functions, and memberships are predictable because they are natural consequences of organizational growth. If not, the organization will decline and possibly cease to exist. Running a successful nonprofit takes an active board of directors and a dedicated staff that is led by a capable chief executive officer.

The Huddleston Group is a full-service management, consulting, and training firm specializing in philanthropy (i.e., campaign counsel, audits, feasibility studies, and creating a culture of philanthropy), opinion research (i.e., donor satisfaction surveys, focus groups, and marketing research), and organizational management (i.e., board transformation, strategic planning, and capacity building).

Huddleston Group Special Offer (click here)

Good Luck!

Ron Huddleston, FAHP, CFRE

President & Founder